|

|||

|

|

|||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

P R O F I L E |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A REINVESTIGATION INTO THE TRANSITION FROM SPA TO SEASIDE TOURISM USING BRIGHTON AS A CASE STUDY part one

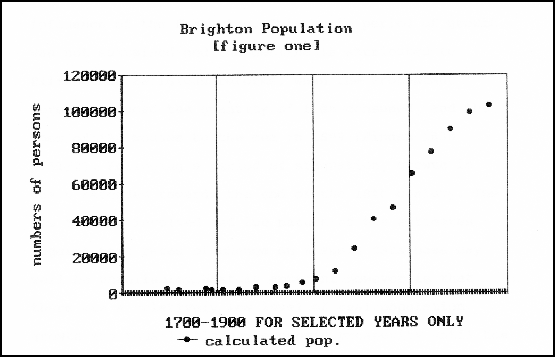

A REINVESTIGATION INTO THE TRANSITION FROM SPA TO SEASIDE TOURISM USING BRIGHTON AS A CASE STUDY part oneUniversity of Birmingham, Centre for Urban and Regional Studies. 2nd Edition, January 1993 with minor revisions 2019. By Dr Bruce E Osborne. BA(Hons). M.Soc.Sc. D. Phil. Picture right - Brighton's Last Fisherman - Rory's Grotto on Brighton Beach. Sussex Great Britain BN1 1EE SYNOPSIS: Using Brighton as a case study, this dissertation seeks to identify whether seaside tourism captured the market opportunity previously held by the spas. This is the popular notion and texts are quoted to illustrate this point of view. In particular, was Russell's sea water cure the catalyst that precipitated the transition from spa to seaside? An evaluation of spa development in Brighton in the context of a reappraisal of spa development overall concludes that the sea water cure was not a major factor in the emergence of seaside tourism. Brighton did develop as a spa but the four aspects of spa development identified merely provided a backcloth for alternative explanations for the prosperity of the late 18th and 19th centuries. The patronage of Royalty is also investigated. This is seen to have a marked effect on, not only the economic wealth of Brighton, but also on the character of the location. Brighton was not only appropriate geographically, the town also offered amusements without the formality of the traditional spas and in this sense, it secured a role for the niche market for Royal patronage. The development of Brighton as a seaside resort followed the period of Royal patronage. Brighton again benefitted due to its geographical location. It also stole a lead on seaside development elsewhere due to the reputation and infrastructure derived from the earlier period of Royal patronage. The development as a seaside resort however attracted a new type of tourist, - certainly not a visitor who would otherwise have sought amusement at a spa and so the character of the town changed accordingly. The conclusion drawn is that the evolution of the spa industry was a distinct and separate process from the development of seaside tourism but that these came together at Brighton as a result of the town's unique geography and circumstances. CONTENTS: Title page, Contents Index, Acknowledgements and Definitions. chapter one: OBJECTIVES, METHODOLOGY AND RATIONALE FOR BRIGHTON AS A CASE STUDY. chapter two: A REAPPRAISAL OF THE EVOLUTION OF SPAS IN THE UK. chapter three: LITERATURE REVIEW ON THE SEA WATER CURE AS THE ORIGIN OF SEASIDE TOURISM. chapter four: BRIGHTON THE SPA. chapter five: ROYAL PATRONAGE OF RESORTS. chapter six: SEASIDE TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN BRIGHTON. chapter seven: DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION. References - by chapter. Appendix: 1. Maps showing the development of Brighton. 2. Memorials to Dr Richard Russell, from photographs by the author. Figures: Figure one - Brighton Population, 1700 - 1900, Ch 4 p14. Figure two - Pier opening by 10 year intervals, 1811 - 1960, Ch6 p3. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: The following have been particularly helpful in the preparation of this dissertation: Brighton Reference Library and staff, E. Sussex County Record Office at Lewes, CURS and Main Libraries at University of Birmingham, Cora Weaver of Malvern Museum, Malvern Reference Library, M Meredith for lecture notes on Brighton. P Sowan of CNHSS for assisting in the accumulation of antiquarian texts. B Smith and B Wheeller for supervision. DEFINITIONS: The following indicates the meanings intended for particular terms used within this dissertation. Bagnio: a bathing house, bath and/or a brothel. Hydrotherapy: water cure by the application of water to different parts of the body, often by douches, baths and wet sheets. Resort: a venue visited by tourists including overnight and day trippers. Seaside: a place visited for the type of pleasure recreation associated with a coastal location. Spa: a place where water is exploited for health reasons as part of a medically recognised 'cure'. This can include natural springs, sea water and artificially made mineralised waters. Thermal well or source: a natural water from an aquifer, that emerges at a temperature higher than would normally be expected due to subterranean heating. Chapter One OBJECTIVES, METHODOLOGY AND RATIONALE FOR BRIGHTON AS A CASE STUDY The dissertation is based on a case study investigation of the evolution of the coastal resort of Brighton in Sussex. 'Brighton is one of many watering places that line the coasts of England. The members of this large family of seaside towns bear some resemblance in appearance and character to their older relatives, the inland spas. In both types of resort, coastal and inland, the main livelihood of the population depends on the holiday industry' (Gilbert 1975 p1). The study seeks to explore two aspects of tourism development; the advent, flourishing and eventual demise of the spa and the advent of the seaside resort. Relationships between the two stages of development are investigated in order to draw conclusions on the transition from spa to seaside. The key question addressed is this: was the transition from spa to seaside tourism part of a continuing developmental process, with the latter capturing the tourism market of the former, as is suggested by many popular authors? The alternative hypothesis is that spa and seaside tourism were distinct and separate social and economic phenomena that happened to come together in Brighton as a result of the town's unique geography and circumstances. Brighton is cited as typifying the processes under investigation and it is where Russell promoted his theories on sea water as a spa treatment and cure. This in turn has led to the notion that the advocacy of sea water drinking and bathing resulted in the economic tourism initiative moving from the traditional spa resorts, most of which were inland, to new seaside resorts. Russell, because of this, has assumed a fatherly role, and Brighton is seen as the leading precursor in the advent of seaside tourism, stances that are questioned in this dissertation. Brighton, unlike the majority of seaside resorts, has the rare distinction of being both a spa town and a seaside resort. Scarborough is the only other major resort that has a similar distinction. Brighton, with its proximity to London, was frequented by all social classes but particularly enjoyed Royal patronage as did the premier inland spas. These factors make Brighton a unique opportunity for a case study, exhibiting the key developmental characteristics of spas as well as those of the seaside resorts. The sources used in this investigation are primarily existing published works. These in turn fall into two categories. First, the use of contemporary published works as indicators of behaviour and opinion at the time of their publication and second, more recent authors' works where issues relevant to spa and seaside growth have been considered. This particularly includes Hembry on spas and Farrant (now Berry) on Brighton. In adopting this approach, care has been taken to ensure that those works cited as typifying the generally held notions are representative. Where particular issues are extracted, attention has been given to ensuring that, they do not lose their validity by being out of context and that they are credible arguments not seriously challenged elsewhere. The first part of this dissertation deals with Brighton as a spa. This is explored in the context of the evolution of spas generally in the UK. In both the evolution of the spa industry overall and the role of the spa at Brighton, alternative interpretations of social history are proposed which vary from the accepted hypotheses. 19th century authors wrote prolifically on the importance of Brighton as a spa. Saunders in 1805 discusses the importance of the chalybeate spring at The Wick quoting observations by Dr Henderson, Dr Tierney and Dr Relhan as to the spring's efficacy. In all, Saunders devotes 72 pages to Brighton spa water. In a substantial book devoted to the principal mineral waters of Europe and including such renowned resorts as Bath, Cheltenham, Harrogate, Pyrmont and Vichy, no other source consumes so much print space as Brighton (Saunders 1805 p331-402). MacKenzie discusses the properties of The Wick ferruginous water, quoting Dr Marcet, in similar vein in 1820, in his extensive observations on European waters (MacKenzie 1820 p 107-109). In the second part, the dissertation looks at alternative factors that could explain the growth of Brighton as a seaside tourism resort. For example, the town's royal patronage, which is relevant to its evolution, is considered. As a seaside, Brighton emerged as a premier resort during the 19th century. Carder describes Brighton as the first authentic seaside town in the UK and quotes Musgrave's nickname "London-super-Mare" (Carder 1990 e15) (Musgrave 1980). Moncrieff used this term in 1902 and it is apparent by his usage that its implied values were well established (Moncrieff 1902 p18). Brighton was not only a participant in the trend towards the development of seaside resorts, it was a leader. Bainbridge notes that the example of Brighton was closely observed and followed by other resorts during the 19th century (Bainbridge 1986 p33). Brighton, or Brighthelmston as it was known before the late 18th century, was thus an active spa and later a premier seaside resort. What took place at Brighton is cited as the founding of seaside tourism. One particular aspect that emerges as important in the analysis of Brighton's growth is timing. Indicators as to when Brighton's economy expanded are therefore reviewed against the evolutionary stages of both the spa and seaside tourism industries. In doing this, modern marketing terms are used in many instances and this reflects the fact that these issues are being considered in a modern light, albeit in a context which prevailed historically. Two conceptual frameworks are considered in this dissertation. These are social and economic. The social sets out to evaluate the activities and motivations of the participants, both tourists and hosts, and to outline the backcloth against which change took place. Included in the social framework is the religious aspect which relates particularly to the early explanations and use of natural springs. The economic considerations are viewed from the commercial standpoint, particularly that of the medical profession. In representing existing texts in this manner, the author believes a more credible picture emerges regarding explanations for the emergence of Brighton as a major resort. This does not invalidate alternative views but enables a deeper understanding to be gained as to the demise of the spas and triggers to the development of seaside tourism. Each issue has modern day relevance as both the seasides and traditional spas seek initiatives in tourism to revive ailing local economies. Chapter Two. A REAPPRAISAL OF THE EVOLUTION OF SPAS IN THE UK "Water symbolises the Great Mother; it is the basis of all life and has universally been used in religious rituals as a means of purification, healing and renewal" (Bord 1985 cover introduction). The importance of water as a vital element of life is a notion of great antiquity. The role played by water in the religious and social practices and beliefs of early man is identifiable through legendary lore. This manifests itself in, for example, the importance placed on such customs as well worship and baptisms. In addition, there is a wealth of archaeological evidence that confirms pre-Christian water cults (Hope 1893 p vii). Bord cites evidence showing the importance of water in Celtic religions. Whilst acknowledging that the hard-surviving evidence lies outside the UK, he produces substantial circumstantial evidence to verify the link between water and religion in the British Isles (Bord J & C p 5-11). This view is shared by Ross. In her study of Celtic cult practice, she clearly identifies water as an integral component of Celtic ritual (Ross 1974). The Celts were not city dwellers or builders in stone and the Roman incursion resulted in a merging of cultures. There is much surviving archaeological evidence illustrating the importance played by water in the society resulting from the Roman invasion of Celtic Britain. Aquae Sulis, now the city of Bath is the most noted of the surviving archaeological remains. The Roman baths at Bath are one of the best-preserved groups of early Romano-British buildings and comprise a bathing complex with a sacred spring enclosure and temple (Stewart 1981 p13). In Roman Britain, Roman imported beliefs such as votive offerings and the worship of the goddess Minerva merged with the earlier beliefs creating an amalgam of deity. The Celtic goddess Sulis merged to produce Sulis Minerva as a goddess of the hot springs responsible for therapy (Stewart 1981 p39). Much Roman mythology however is a development of earlier Greek practice. 'Hippocrates, Horace and Tasso all observed that springs which faced the sun had healing qualities' (McMenemey 1952 p1). In his review of the springs of Ancient Greece, Glover looks at the distribution and use of natural water sources. He concludes that such sources played a vital healing, religious and practical role in early Greek society. In particular he notes that there is no other literature which mentions spring water so often and discusses the wide variety of waters available and the cures associated with them (Glover 1945 p28 etc). The Athenian Agora or simple fountain house was developed by the Romans into the more elaborate Nymphaea. These were fountains dedicated to Nymphs. The Greek origin was grottos with springs but these were transformed by the Romans into monumental hydraulic public works (Miller 1982 p17). The Roman influence resulted in major spas being established throughout Europe. Such aquae were regarded as places not only for cleansing and social intercourse, but also as places of medical treatment and worship (Jackson 1990 p3). These early origins are important in the context of Brighton, as will be seen in the following chapters. Following the demise of the Roman Empire and its influence in Britain, the spa culture deteriorated. Alongside the ancient celebrated spas, however, was the more localised practice of pilgrimage, healing and worship related to Holy Wells. Initially associated with the pagan religions, Christianity enveloped the practice and legitimised it. The varying curative properties of different natural waters had been known since time immemorial. The absence of modern chemistry resulted in the properties being accredited to mystical influence and saints were often ascribed to particular springs. Such springs were widely distributed throughout the UK in considerable numbers. Many of them have subsequently become the subject of further exploitation and their healing properties continue to be recognised. With a few exceptions, the majority incorporated small built structures containing a natural spring with the minimum of facilities. They were used by the populace at large and because their mineral content varied as a result of the underlying geological strata, vast distances were sometimes travelled to use a well suited to a particular affliction (Lane-Davies 1970, Hope 1893, Jones 1954, Walters 1928, Quiller-Couch 1894, Naylor 1983, Logan 1980, Source 1985+ et al.). The chalybeate well of St Ann at Hove is an example. These iron bearing waters were known long before Brighton emerged as a spa or seaside tourism resort (Carder 1990 e79). The holy wells were not always looked upon with the approval of authority however. "Among the dramatic actions of Henry VIII government at the Reformation was the closure of many Holy Wells" (Hembry 1990 p4). Hembry quotes an estimate of about 450 holy wells based on Hope at about this time (1530s) but publications cited elsewhere in this chapter suggest considerably more, without putting precise numbers to paper. At the Reformation a new approach emerged to bathing and water use. Meetings at the wells had become associated with Catholicism and masked recusant plots. Now the growth of the medical profession, together with secular learning and the need to allow healing waters to be consumed domestically, resulted in traditional habits being given a new air of authenticity with emphasis on medicinal qualities confirmed by analytical observation. Dr William Turner took on the new religion and science, publishing the first treatise on baths in 1562. This pioneer writer in the field sought to popularise knowledge of the healing properties and to bring an end to neglect and decay, particularly at Bath. This included upgrading to continental standards the various mineral water sources and facilities (Hembry 1990 ch.1). Bath, Buxton, Harrogate and the failed Kings Newnham became the Tudor precursors of the English spas with other centres like Bristol Hotwells and Holy Well (Flintshire) becoming important regional spas by the end of the 15th century (Hembry 1990 p18, Robertson 1866 p17). Two particularly important early spas were Tunbridge, "discovered" in 1606 and Epsom in 1618 (Home 1901 p43, Farthing 1990 p1 introduction, Havins 1976 p20). Both of these were to have later significance in the development of Royal patronage and endorsement which was key to the subsequent development of the spa industry. The new social habit of taking the waters spread rapidly in the 17th Century and the important spas developed infrastructures to accommodate this new form of tourism. In spite of the civil war breaking out in 1642, the vogue for going to the baths and wells continued and Stanhope's analysis of cures of the time notes an equal dispersion between the gentry/nobility and others (Hembry 1990 p52). Facilities at the rural spas particularly were basic. With central government now paying little attention to the spas, the entrepreneurs saw the potential for a new leisure market and the social needs of the elite became the raison d'etre. The 18th century saw the success of the turnpike system resulting in road improvements. Transport thus stimulated further spa development. Bath remained for a long time the premier spa but had been superseded by Tunbridge Wells in the 17th century. Better management of the well areas and the associated social life resulted in growing popularity of the spa experience and it is interesting to note that Celia Fiennes in 1697 gave Scarborough only a limited approval because of the restriction of amusements due to the preponderance of Quakers in the town (Morris 1947 p92). The development of seasons resulted from competition between Epsom, Tunbridge Wells and Bath all of which received Royal patronage. By 1719 complaints were made about Buxton; it had become a disreputable place with visitors arriving for pleasure rather than medicinal need (Hembry 1990 p94). Such a change of priorities was to become the hallmark of spa tourism during this era. Bagnios, initially establishments for bathing for health, deteriorated into brothels. A variety of treatments and entertainments were available for the wealthy at both the spas and their replicas, the bagnios or bath houses. The overall trend was a lowering of the moral tone of establishments as the wealthy and the common people pursued the social and leisure aspects to the full (Turner 1967 ch.7). It was in 1705 that Richard Nash first tried the gaming tables of Bath and it was he who, more than any other single person, was to restore a respectability to the spas (Melville 1907 p41). Following a dual in which the Master of Ceremonies at Bath was killed, Nash took up the appointment (Turner 1967 p59). Beau Nash as he became known, restructured social interaction at the spas, particularly Bath, with sets of rules for social etiquette and provided order where there had been chaos. "Under the rule of Nash, Bath soon became a place of great social importance in the kingdom" (Melville 1912 p147). Tunbridge Wells however had the advantage of proximity to London and by the 1730s Nash had extended his interest and direct involvement there, formalising the interaction of the classes and directing the social activities of the town. Nash died in 1761 (Farthing 1990 p3) The 18th century thus saw a change in emphasis and tone at the principal spas. From an era of what many would describe as "irrepressible debauchery and open licentiousness" emanating from the 17th century, the social style changed (Melville 1907 p279). From 1705 to late in his life, Nash's influence at the leading spas resulted in the introduction of "a formalised pattern of behaviour for the benefit of the higher bourgeoisie who joined their betters at the waters." New standards of behaviour became the pattern for the industry (Turner 1967 p59, Hembry 1990 p137). This change in style during the 18th century is, arguably, particularly significant for Brighton. It coincided with the first signs of Brighton emerging as a significant spa resort. It will be seen in later chapters that both the medical profession and the gentry started to consider Brighton as a tourist destination from the mid-18th century onwards, at a time when strict rules of behaviour and etiquette were being applied at the established inland spas. During the 18th century the wealthy frequented the spas in increasing numbers, aided by further improvements in transport and the social prestige of holidaying with the fashionable as well as securing some health benefits. There were also developments on the medical front which were to have far reaching effects. Early legitimisation of the properties of mineral waters had come from religion; now science was to become involved. The development of abilities to deal with dissolved gases and a growing awareness of the properties of dissolved compounds resulted in scientists seeking to explain cures in chemical terms, rather than as the hand of God. Outdoor recreation in a quality country environment was also realised to be an important aspect of a cure (Hamlin 1990 p68-71). A leading figure in this new approach was Dr William Saunders. Saunders, publishing at the turn of the century in 1805, commented on the chemical characteristics of, amongst other sources in the UK and Europe, the Brighton chalybeate well, as has been outlined in chapter one (Saunders 1805 p331-402). As the 19th century progressed, the discovery of new elements made it difficult to argue that a water's properties were due to anything other than elements hitherto discovered or undiscovered (Hamlin 1990 p78). The mystique of the waters was thus replaced by scientific knowledge. Addison states that by the early 19th century the patronage of the spas started to noticeably decline (Addison 1951 p1). Hinde dates the decline slightly earlier after 1790 (Hinde 1988 p189). Earlier claims extolling the virtues of certain waters, now proved spurious, were a key factor in the decline together with the realisation that much could be achieved by adding minerals to water. For the first time, manufactured mineral waters could be justified on scientific grounds. New artificial mineral waters supposedly offered all the benefits previously only bestowed by medically supervised natural springs (Hamlin 1990 p81). The medical profession, in a move to secure it's future with the now questionable natural mineral waters, sought new market opportunities for water sources. One answer came in the form of hydrotherapy. In Bavaria, Sebastian Kneipp, 1821-97, a parish priest, developed systems of healing based on a variety of cold water applications and natural medicaments. The village of Worishofen was quickly over run with tourists seeking cures and his methods gained considerable world-wide acclaim (Kneipp 1893). With similar timing, Vincenz Priessnitz, 1799 - 1851, from Grafenberg in Austrian Silesia, was sentenced to imprisonment for practicing water cures along similar lines to Kneipp. The judgement was reversed and in 1838 the Imperial Home Office investigated, recommending that the enterprise was to be encouraged. According to Nott, Priessnitz started cures in 1829 and within ten years was dealing with 1400 patients per annum (Nott 1900, Weaver 1990 p3). Hydrotherapy dramatically developed from that moment and numerous publications in the UK emerged from 1843 onwards detailing the treatment (Turner 1967 p142-162). There is evidence to suggest that what became known as the technique of hydrotherapy was well known before it revolutionised the cure in the 1840s. Writing in 1702, Floyer comments that many ancient practices in "physick" have been revived. Pliny and Seneca testify to the use of cold bathing which was invented by the common people. The "Aegyptians, Greeks and Romans" go into water in shirts and wet linen. At Willowbridge, Floyer notes that they wear wet shirts all day and that palsey and rheumatism was cured after riding three miles in wet clothes (Floyer 1702 A2, A4, B2, 141, 214). Even in Malvern, where Dr Wilson was celebrated as the person introducing Hydrotherapy to England in the 1840s, the Holy Well and Ditchfords Well were being used for hydrotherapy as early as 1800 (Weaver & Osborne 1993). The 19th century marketing of hydrotherapy by the medical profession had therefore an element of opportunism which was to have implications for Brighton. Both Kneipp and Priessnitz came from mainland Europe and were using hydrotherapy in their own immediate localities. It was the medical profession which exploited the practices of hydrotherapy by extending the legitimisation and marketing of the technique in England. Claridge published his view in 1843, following a recommendation to visit Priessnitz in 1840 (Claridge 1843 p19). Smethurst published his views, also in 1843, after several months in Grafenberg (Smethurst 1843 p xii). In 1845, Wilson of Malvern had built Priessnitz House following the publication of his two works on hydrotherapy. Gully, also at Malvern, published in 1846 and subsequently became one of the leading physicians of his era (Denbigh 1981 p180)."Hydrotherapy had caught the eye of the public" (McMenemey 1952 p10). The result was a revolution within the industry and quickly other establishments followed. The nature and significance of this revolution has hitherto been omitted by authors on spas. In 1844 Ben Rhydding was founded as a hydrotherapy centre in Ilkley and by the 1870s both Mr and Mrs Smedley of Matlock were publishing manuals for what was perhaps the largest of all UK hydrotherapy establishments at Matlock Bank, Derbyshire (Smedley 1870, Smedley undated, Denbigh 1981 p 186). Behind this revolution was a clear market opportunity. Hydrotherapy, as a residential programme, was particularly suited to nervous fatigue, a disorder of great men and their spouses. This provided an opportunity for private treatment without the necessity of certification which the 1828 and 1845 Lunatic Asylums Act made necessary for private asylums (Browne 1990 p106 & 113). The mid-19th century thus saw the spa industry change its raison d'etre completely. The taking of the natural waters for their mystic healing qualities declined. The new skills of hydrotherapy brought about not only a change of practice but also a relocation of the key centres. Malvern, with its high-quality environment and pure water became popular but many of the more traditional spa towns lost their appeal, particularly if they failed to take on the new techniques or suffered from urbanisation. Brighton was in the throes of its own changes at the time. It will be shown in subsequent chapters that, as hydrotherapy grew in importance, Brighton pursued alternative commercial opportunities. Hydrotherapy, linked to taking the waters, remained an important industry well into the 20th century when it was eventually ousted by technology and new approaches in medicine. The spas fought back however. There was a move in the 1920s to argue that radioactivity gave certain natural waters healing characteristics but this was short-lived as a result of rapidly developing scientific knowledge. "The outstanding feature in the Bath Water is its high degree of radioactivity and there is strong reason for thinking that this factor is responsible for its physiological properties" (Spas Federation c1930 p7). This followed a report on the radioactivity which suggested a link between the therapeutic value and radium content (Munro 1928 p7). Possibly because of the problems experienced by Marie Curie in later life and the ability to replicate such treatment in controlled conditions, the Spas Federation failed to create significant new initiatives for the spas. As modern medicine and methods superseded the historic approaches, (Bower 1985 p3), the spas quietly became part of the heritage in the UK, albeit still practicing hydrotherapy elsewhere in Europe up to the present day (Johnson 1990 p124-126, Gillert 1990). Chapter Three. LITERATURE REVIEW ON THE SEA WATER CURE AS THE ORIGIN OF SEASIDE TOURISM. A wide range of published material exists on the history and development of seaside tourism and its possible origins in the spa industry. The particular aspect that is under review is the extent to which the origins of seaside tourism can be traced to spas and to Brighton in particular. To review everything published would be an impossible task. A selection of works has therefore been appraised as being indicative of the line of reasoning generally adopted and now under scrutiny. Where possible, key source books have been included. Brighton developed a variety of initiatives over time that led to economic growth. The resulting prosperity brought about rapid change in the town and this in turn caused the demise of earlier activities. The Victoria County History of Sussex, probably the most used authority on Brighton's past, notes that throughout the 18th century, Brighton was recommended as a health resort by physicians. Yet by 1819 Mrs Fitzherbert is quoted as saying; "you would hardly know Brighton, it is so enlarged since you were here." By 1822 the race course, chain pier and other seaside features were being established illustrating the metamorphosis that was underway as Brighton changed from spa to seaside resort (Victoria History of Sussex 1940 p284 & 250). One recurring feature of historical accounts of Brighton and the origins of the seaside resort, is the role of Dr Richard Russell, who, in 1753, published an English translation of an earlier work advocating the use of sea water as an extension of mineral water health cures (Russell 1753). This use of sea water is cited as fundamental to coastal locations increasing substantially in their appeal and some authors argue that the nobility were the trend setters. Murray sees Russell as the instigator of the Royal patronage at Brighton, in the late 18th Century, which in turn was the catalyst for Brighton's growth. Supposedly, Royalty were attracted to Brighton by Russell authenticating the use of the sea water as part of a spa cure (Murray in Dale 1979 p9). Burton describes Russell's in even stronger terms, suggesting that the influence was direct, placing less stress on influence: 'Brighthelmston, a small, dirty, unattractive spot, became fashionable and beautiful Brighton in a space of about 30 years, a metamorphis almost entirely due to Dr Richard Russell whose book The Uses of Sea Water in Diseases of the Glands was an immediate success.' (Burton 1967 p383/3). A similar view is reflected in the 19th century popular tourism literature. 'This famous watering place owes its present prosperity, in the first place, to a physician, Dr Russell of Lewes, who removed hence on 1750'. (Newnes 1895 p25). A detailed evaluation of Russell and his work is carried out in chapter four. His impact is typically reflected in the works of the School of Architecture which identify Russell as a powerful advocate of the curative properties of sea water. 'He established his own reputation and, indirectly, that of Brighton by publishing a book on the uses of sea water for the treatment of various illnesses' (School of Architecture, c1990 p6). Before Russell the small seaside resorts were not to be compared with the inland watering places. The sea was a hostile environment but a growing participation in sea bathing and the influence of Russell, arguably, resulted in changing attitudes. 'Visitors came to the seaside for the same reasons as the spas, and amongst them health and pleasure are not easily disentangled. There were three ways in which the health might be benefitted - in air, drinking the water, and bathing' (Pimlott 1947 p56). Pimlott sees the popularity of the seaside as a natural consequence of the spas. Suddenly sea water was the new panacea and enthusiasm was directed towards this innovation in medication. Quoting Smollett, who was a great social observer of the time: 'Were I to enumerate half the diseases which are everyday cured by sea bathing' wrote young Melford in Humphry Clinker, 'you might justly say you had received a treatise, instead of a letter' (Pimlott 1947 p52-55). Described as instrumental in reviving Brighton's fortunes, Russell's portrait hangs in the Brighton museum. The degree to which he is seen as the founder of Brighton and in turn seaside tourism, is illustrated by the commemorative plaque that hangs on the site of his former house. The plaque is on the southern face of the Albion Hotel and reads 'If you seek his monument, look around' (Carder 1990 el64 and illustrated in appendix 2). Dale, in 1950, reviewed the life of Russell and concluded that 'From this state of decrepitude the town was only rescued in 1750 by the arrival of the real founder of modern Brighton... The publication of his work was one of the first occasions upon which attention was directed at the usefulness or attractiveness of the sea in England and was thus not only the foundation of the future of Brighton, but in fact the whole English sea side' (Dale 1950 p18-19). The influence of sea water cures therefore, supposedly, went well beyond the bounds of Brighton. Many authors interpret the development of seaside leisure as secondary to the curative value of the seaside experience as the coastal resorts became the new spas. This transition from inland spas to seaside resort is covered in general terms by such authors as Brendon. 'Like the spas, which they outstripped, seaside resorts gradually changed from health centres to havens of pleasure' (Brendon 1991 p11) The assumption is very much one of a transition of patronage from spas to seaside. A number of quotations are now reproduced to illustrate the supposed close interrelationship of spa and seaside tourism evolution. In the context of a discussion on the development of spas: 'During the 18th century there was a considerable increase in sea bathing as the developing merchant and professional classes began to believe in its medical properties as a general pick-me-up' (Urry 1990 p17). 'The seaside resorts were modelled on and superseded the inland health spas, which had become as important as centres of social life as for their therapeutic qualities. To that extent the resorts were derivative, but they were also adaptable.' Later it is noted that by the 1880s seaside resorts were rapidly overtaking the Inland spas (Bainbridge 1986 p19 & p109). 'More extensive reminders of the early days of tourism lie in the spas and seaside resorts whose origins were linked to the pursuit of health' (Murphy 1985 p17). 'Many factors are concerned in the origin of seaside resorts, but the medical profession is primarily responsible for their birth' (Gilbert 1975 p9). The picture that emerges from the literature review, is that the new seasides captured the tourism market at the expense of the older established spas. The reasons for this, in the literature, include the pursuit of health cures following Russell advocating sea water as a spa treatment and the pursuit of leisure. Russell's work thus, supposedly, performs the role of catalyst in this transition and, because of his location at Brighton, puts this town in the premier, pioneering position. This reinforces the observations made in chapter one as to why Brighton makes a unique case study. It has already been noted in chapter two that, by the early 19th century, the traditional spas were in decline. If the demise of the spas can be even partially attributable to the swing of tourists to the coastal resorts, then Russell was the architect of a revolution that fundamentally changed the nature of tourism in the UK. Closer scrutiny of the circumstances however suggests that this hypothesis is too simplistic. A number of questions arise which cast doubt on what appears to be a clean and tidy explanation for the origins of seaside tourism. Prior to Russell, the spa industry was extensive, highly organised, and well endorsed as a cure by the medical profession, as has been shown in chapter two. Its origins went back to the earliest civilisations and what had emerged by the 18th century was a social and curative regime of the highest order. Was the discovery of seawater as a cure so potent as to eclipse a whole sector of medical practice and expertise as practiced in the established spas? It has been noted in chapter two, that one reason for the demise of the spas was the explanations that the new skills of chemistry were able provide in understanding of the composition of mineral waters and their physiological action. Chemistry superseded the hand of God in explaining the cure and led to the ability to replicate the natural mineral spring artificially. A second question that is raised concerns the motivations for seaside tourism. The leisure aspect was an important motivation for frequenting a spa or the seaside. Earlier it has been shown that at the spas, society leisure was carefully structured by Beau Nash who initiated the social etiquette and formalisation of the spa seasons. This prompts the question, was it the same type of leisure that motivated seaside tourism, and, were the visitors of similar social class and background? In order to gain a deeper understanding of the processes at work in Brighton and to appreciate the role of Russell in those processes, this dissertation now goes on to investigate in detail Brighton as a spa. Chapter Four. BRIGHTON THE SPA. 'In otio sine cura bibe, Et spem fove salutis' (Franz 1842 title page; from the Royal German Spa at Brighton guide). Brighton's claim to being an active participant in the spa tourism industry is based on the development of several water-based resources; 1) the natural mineral water of St Anne's spring; 2) Russell who promoted the sea as a spa water; 3) the establishment of a number of bath houses; and 4) artificial mineral water manufacture. The first of these resources, St Anne's natural mineral water spring, was developed rather late in the history of spa tourism development in the UK. As has been noted in chapter two, the iron bearing waters of the Wick (now Hove) chalybeate spring were known long before Brighton emerged as a spa or seaside resort (Carder 1990 e79). Underwood indicates that the St Anne's spring at Wick, was once a copse where shepherds watered their flocks (Underwood 1978 p126). This reference probably comes from Relham, who in 1829 remarked on the legendary extraordinary fecundity of the sheep who drank its waters (Relham 1829 referred to in Gilbert 1975 p64/5). Whilst the evidence of the early use of the waters for health purposes is circumstantial, it is apparent that the Wick spring was one of the earliest waters used for health cures in Brighton. Russell supplied a wooden pump room and basin about 1750 at St Anne's well and prescribed the waters to patients. At this stage the spring had likely minor significance as Russell failed to mention it in his account of the natural properties and uses of all the remarkable mineral waters in Great Britain and of foreign mineral waters which was a supplement to his sea water dissertation. (Russell 1769 p177-367). Later the wooden pump room was replaced by an Ionic portico. Denbigh suggests a date of about 1800 for the replacement although Carder dates it later at about 1830 (Carder 1990 e79, Denbigh 1981 p134). The spring was not promoted nationally as a significant source until Saunders wrote in 1805, as briefly referred to in chapter one. Saunders devoted 72 pages to St Anne's Well which had only previously been mentioned in local guide books (Saunders 1805 p331). Monro's earlier Treatise on Mineral Waters, 1770, an important two volume work on the mineral waters of Europe makes no mention of Wick (Monro 1770). Mackenzie, writing in 1820 his directory of mineral waters and uses, comments on the chalybeate spring at Brighton but relies heavily on Saunders' earlier work (Mackenzie 1820 p 107). The source declined in popularity during the 19th century and by 1850 the area was converted to a private pleasure Carden (Carden 1990 e79). Granville, in his well-known authoritative work in 1841 on the spas of England makes only a passing reference to it (Granville 1841 p577). Brighton's natural spring water source thus had a brief period of national fame during the early 19th century with 1800 - 1830s being when the source was at its height of popularity. During this period, evidence indicates that numerous physicians endorsed the well's efficacy (Gilbert 1975 p65). Prior to this it had only local appeal and as such did not enjoy the reputation and awareness of the established spas, many of which had been active since the 17th century. After the 1840s, in accordance with the changes taking place in the industry overall covered in chapter two, St Anne's spring fell into decline. Russell's development of the St Anne's spring, was minor compared to the impact that he had on sea water as a cure, if much of the subsequent published accounts are to be given credence. Sea water is the second of the water resources developed at Brighton. Russell was not the creator of the sea water cure however. It has already been shown that the Greeks and later the Romans paid considerable attention to the healing properties of mineral waters. One of the most celebrated spas in antiquity was Baiae, on the Bay of Naples. This Roman spa became the most fashionable of all resorts and was noted for licentious living as much as for the waters. This was a model that Brighton followed. Pliny not only wrote about Baiae, he also wrote extensively about sea water, listing a wide range of medical uses (Jackson 1990 p5). The Greek Herbal of Dioscorides also notes the use of sea water for curing a variety of afflictions (Gunther 1959 p608/19). Sea water as a curative medium was well established in the classical world. Sea water as a cure occurs occasionally in post classical writings. Pimlott identifies in 1620 the use of sea water with herbs for those too sick to visit Bath and recommended for gout in 1667 (Pimlott 1947 p51). In 1702, Floyer was noting that cold salt baths from seawater were being used for curative purposes (Floyer 1722 p21 item 4). Russell acknowledges being influenced by the sea water purges set out in "The Domestic Companion" which he read in 1730 (Musgrave 1981 p52). Thus, sea water as a cure was known but not significant when Dr Russell first came to publish his dissertation on sea water in 1752 (Pimlott 1947 p52). Russell, in his dissertation, considers both bathing and the internal use of sea water as a cure and quotes extensively from case histories to support his proposition (Russell 1769 p162 etc.). Pliny similarly advocated taking sea water internally and externally. (Pliny 1856 p496) Russell's work, which was far more extensive than that of Pliny, can be seen as a development of the classical thesis and in fact Russell acknowledges Pliny in his text (Russell 1769 preface xi). Russell first published in Latin in 1750, quickly following up with an English translation. Carder suggests that, from about 1740, Russell had sent patients to Brighton, from Lewes where he practised, for the sea water cure. In 1753 Russell built a house on the sea front at Brighton where the Albion Hotel now stands. He moved to Brighton at the age of 66 but his presence at Brighton was limited due to his demise in 1759 (Carder 1990 e164, see also appendix 2). His book continued to be republished, the fifth edition being available in 1769 (Russell 1769 title page). Russell thus had a time span of influence starting about 1740, peaking after his publication in 1750. Any merits in his cures likely resulted from the mild disinfectant action of sea water on the body and the absorption of iodine, useful in cases of goitre (Musgrave 1981 p53). This enabled him to make a worthwhile living from his treatments. It also enabled the enterprising fisherfolk of Brighton to offer their services as bathers and dippers, a profitable diversification (Musgrave 1981 p54). In evaluating the importance of Russell, his work needs to be assessed in the context of, not only other external influences affecting spa and seaside tourism which are considered in detail throughout this thesis, but also in the context of two factors directly relevant to his works and the influence with which he is accredited. The first of these relates to the medical profession at the time. Outlandish cures were good commercially and fortunes were made as a result. For example, Page in 1763 published "Receipts for preparing and compounding the principal medicines made use of by the late Mr Ward." Ward is described as 'One of the quackiest yet most reputable medics of the period. He treated many of the great names of the day. Fielding refers to him on his voyage to Lisbon. It would seem that he only had one treatment failure. A person who took Sweating Powders for 32 successive nights.' (Youngs 1992 item 200) A Dr Thomas Beddoes, in the 1790s, experimented with pneumatic medicine. His Pneumatic Institute practiced the inhalation of nitrous oxide (laughing gas) as a means of cheering patients (Turner 1967 p112/3). Thicknesse, at Bath in 1780, proposed that inhaling the breath of virgins promoted health and long life (Hinde 1988 p70). It was not perhaps only the breath of the virgins that restored a certain vigour to the patient. Dr Russell was a believer in the premise that desperate diseases required desperate remedies. He experimented with concoctions of wood lice, vipers' flesh, tar, snails and crabs' eyes to be taken with a draught of sea water (Musgrave 1981 p52). This was certainly an age of imaginative medicine! Even Dr Russell's practice was taken over, in 1759, by a Dr Relham who had previously been forced to resign in Dublin due to prescribing Dr James's fever powder. 'The strict line of division that exists today did not separate the quack from the qualified practitioner' (Sitwell 1938 p52-53). It was in this climate of innovative medicine that Dr Russell promoted the sea water cure. Even the later advent of hydrotherapy was seen as a quack cure by the profession (McMenemey 1952 p11). The second factor that needs to be accommodated in evaluating Russell's influence is sea water bathing for leisure. This is more difficult because of the difficulty in distinguishing between a quick dip for a cure and a dip for pleasure. Bathing for leisure in the sea was long established before Russell's publication. Bates notes that in 1577, at Naples, the custom was to bathe in the sea previous to paying one's devotions (Bates 1987 p145). Several authors identify bathing at Scarborough in the 1730s. Setterington's print of 1736 is cited as first evidence of bathing machines. Margate followed in the 1750s (Swinglehurst 1978 p70, Pimlott 1947 p58 et al). Early bathing was a serious business in a hostile environment and the motivation certainly included an element of cure in those early years (Urry 1990 p17). In order to make matters less uncomfortable, indoor bathing in sea water was established in Brighton after 1769. Thus, Russell was pre-empted in advocating sea water bathing as well as the internal use of sea water. Russell was careful to point out that he developed his ideas from the works of others (Gilbert 1975 p58/9). The picture that emerges of Russell, therefore, is one of a person who added weight to the use of sea water as a cure at a spa resort. His era was relatively short lived with his greatest influence being probably shortly after his death in 1759 when his book was reproduced in several editions. Also, his cure was proposed at a time of remarkable innovation of cures generally and was initiated when sea bathing was becoming popular anyway for leisure purposes. The low level of impact that Russell's sea water cure had can be gauged from tourist numbers at the time. Visitor numbers for Brighton in 1760 are estimated at only 400 per annum and it was not until the end of the 18th century that they rose to above 4000 per annum (Gilbert 1975 p92). Russell's enthusiasm for sea water was followed up by others and in 1768, a Dr John Awsiter locally published a dissertation on sea water uses and used this as the justification for his indoor baths (Awsiter 1768). Indoor bath houses are the third water-based resource developed as part of Brighton's spa industry. There is evidence to suggest however that the cure was not the only attraction with the bath houses. Sea water was the most readily available water supply in large quantity and indoor sea water bathing was first established in Brighton in 1769 by Awsiter with a purpose-built baths. Later known as Creates Baths, they were demolished in 1861 (Havins 1976 p110). Awsiter published one of the first guides to Brighton. It was not indoor sea water bathing that Awsiter primarily promoted however, it was the likening of Brighton to Baiae where the ancient Romans retired for bathing and pleasure (Musgrave 1981 p57). After 1769 a series of developments relating to indoor bathing took place: In 1786, Mahomeds Baths opened in Kings Road. These were supposedly the first Turkish or vapour baths in Britain and included massaging services. Numerous "cures" enhanced the popularity and Royal patronage followed (Carden 1990 e7). There is little doubt however that Mahomed's was a development of the well-established bagnios elsewhere but incorporating sea water which was of course readily available. Turner notes that the routine of sweating, rubbing, stretching, scraping and sluicing was the basis for the establishment of bagnios throughout Britain. Establishments opened in London from the late 17th century and quickly became dens of iniquity. Casanova, visiting England in 1763, went to a Covent Garden establishment for a magnificent debauch with the prettiest girls in London, for six guineas (Turner 1967 c105-107). Quin took his lady friend to such an establishment in the mid-18th century, "The first time in her life she had been to such a place. Her terrors were extravagantly great, till she thought there was no further danger (from her husband) .... and gave a full loose to the indulgence of her passion" (Hinde 1988 c120). A feature of the bagnios was the addition of minerals to create artificial waters unattainable in nature (Turner L967 p105). Mahomeds Baths similarly used herbs and oils as well as a great variety of manipulative techniques in treating particularly the novelty seekers (Turner 1967 p110). The suggestion is that in Brighton, after the mid-18th century, pleasure became as important if not more important than the cure as the motivation for the bath houses and associated facilities. This was at a time when influence of Nash at the inland spas was establishing strict rules of behaviour and etiquette, as described earlier. In Brighton the early 19th century saw a whole series of baths opening, reflecting the growing prosperity of the town. In 1803 Williams's Baths opened in the Old Steine. 1813 saw the Artillery Baths open. Brills' Baths opened in 1823. After the 1850s however, popularity declined for individual facilities and the old establishments disappeared or were modified to encompass communal bathing which started to become popular with the opening of Lamprell's Bath in the 1840s (Carden 1990 e7). This change of practice was important for Brighton and is discussed further later. Brighton's "old style" bath houses therefore appeared in the latter quarter of the 18th century and survived until about the 1840s. In 1825 a significant development took place in Brighton. This not only led to new approaches to "the cure", it was instrumental in generating an entire new industry, the manufacture of artificial mineral waters, which continues into the present day elsewhere. This gave rise to Brighton's fourth water resource developed as part of the spa industry. Against a background of: 1) a development of the science of chemistry in understanding mineral water contents (see chapter two); 2) the creation of cure facilities with "apparatus that impregnated the bathing pool with artificial mineral waters of a purity unattainable in nature" in the bagnios (Turner 1967 p105); and 3) the work of Jacob Schweppe in creating artificial mineral waters in Germany and Geneva around 1783 (Simmons 1983 p13); .... Professor Struve founded the Royal German Spa at Brighton. 'It was an artificial spa where chemical imitations of well-known spa waters could be bought and either taken away or drunk on the premises' (Hollingdale 1979 p117). After meeting Struve, Granville refers to Struve's activities in his 1837 publication of his tour and assessment of German spas. When Granville first wrote in 1828, Struve had several years experience in Saxony, of producing artificial mineral waters and there was high expectations from the results of Struve's labours. Granville goes on to refer to a Privy Council investigation into Struve's processes at Brighton and the extension of the patent rights as a result. By the 1830s Granville estimates 400 - 500 patients of note per annum "find it a pleasant and easy mode of recovering their health" at Brighton with similar establishments now in several German, Polish and Russian cities (Granville 1837 p240-242). Struve died in 1840 but his work continued to be endorsed by the profession. Struve had originally contrived his artificial waters in an attempt to replicate his own successful treatment at German spas, following an explosion during a chemical experiment which injured him (Franz 1842 p6). By 1841, Granville saw two reasons for the unwell to go to Brighton. These were, first, convalescence: the recovery after the disease has been removed; and second: for the "real" patients to visit Professor Struve's manufactory (Granville 1841 p571). St Anne's well was not considered a serious cure by this time and Granville viewed sea water baths merely as not objectionable (Granville 1841 p562). When the medical profession, at the spas elsewhere, was starting to capitalise on hydrotherapy, as outlined in chapter two, Brighton was receiving acclaim for its artificial waters. Brighton thus diversified as a spa, but not into hydrotherapy. The popularity of artificial mineral waters as a cure declined in tandem with the decline in the patronage of natural waters. This was due to the changes going on in the medical profession overall, particularly new types of treatment involving drugs and manufactured curative products linked with the scientific advances in chemistry. During the 1850s Struve's pump room closed; instead the company concentrated on the production of bottled mineral waters as soft drinks, up until 1965 when the building became redundant (Carden 1990 e138). Of the four water-based resources that Brighton developed during the 18th and 19th centuries, an evaluation of their importance can be gauged by considering each in the context of the economic growth of the town. One measure of economic growth is the rate and timing of population growth and in this aspect the work of Farrant is invaluable for the population estimates made for particular years in the 18th and 19th centuries (Farrant 1976). Unlike modern times, early Brighton was not closely monitored statistically. The use of such estimates however provides the best available indicators of change in spite of the fact that such data can, inevitably, be challenged (Farrant 1980 p15).

The population of Brighton, based on Farrant, is shown on the above figure. The vertical grid represents 50-year intervals and the individual plots are calculated populations from a variety of sources particularly the census from 1801 (Farrant 1976 p4, Carden 1990 e127). It can be seen that the population of Brighton did not start to substantially grow until the 19th century. Throughout the 18th century, estimates suggest population levels in the region of between one and four thousand persons. The start to real growth is identifiable in the 1790s. Carder analyses the data on a logarithmic scale and as a result detects high rates of percentage increase year over year initially from the 16/17th century influence of the fisheries. This early period of growth was not sustained and the decline is attributed to Elizabethan religious reforms, when the Protestant worship reduced the quantity of fish consumed, and the loss of 130 houses to the sea in 1699 (Finden 1838 p151/2). Following a period of stagnation, growth is again recorded towards the end of the 18th century. The low figures involved and the nature of the estimates suggest that rates of change on a small data base may well be unreliable. What is apparent however is that there was a relatively low level of real population growth and thus little new economic prosperity until the close of the 18th century. The four water resources developed as the key elements in Brighton's spa era can thus be evaluated in the light of the population data. The natural mineral water spring of St Anne's was at its height of popularity from about 1800 - 1840. This would coincide with a growth in economic prosperity for Brighton. St Anne's spring however was a late entrant into the natural mineral water cure market at the spas. In the early 19th century the mineral water spas were suffering some decline as was noted earlier. St Anne's failed therefore to develop and enjoy the level of patronage associated with the established spas. St Anne's spring thus fails to provide a convincing reason for substantial economic growth. Russell's promotion of sea water similarly fails to provide a convincing reason for economic growth. His cure and its popularity came about during the third quartile of the 18th century. Economic growth came later. Also, as has been previously noted, his cure came at a time of remarkable innovation of cures generally and was initiated at a time when sea bathing was becoming popular anyway for leisure purposes. To suggest that his influence on the use of sea water, after his publications in the 1750s, supposedly dramatically altered the destiny, not only of Brighton, but of the entire medical profession and the tourism industry by creating seaside tourism is arguably unsustainable. This view is supported by Pimlott who indicates that it would be wrong to ascribe to Russell the main responsibilities for the popularity of the seaside (Pimlott 1947 p54). It has been shown that changes in medicine resulted in changing attitudes towards spa treatments during the 19th century and Russell's system would have been similarly eclipsed as a cure. The two later developments of water resources in Brighton, the establishment of a number of bath houses and artificial mineral water manufacture, did coincide with economic growth in Brighton. In the case of the former, the motivations had moved away from the traditional cure to more pleasurable pursuits. This is considered in more detail later. In the case of the latter, after the mid-19th century the German Spa was a manufactory only and had little influence on tourism, either spa or seaside. The conclusion that remains is that the natural mineral water and sea water spa cures at Brighton had little direct effect on subsequent economic prosperity and it would be wrong to credit the sea water cure with the founding of seaside tourism. The two derivatives, the bath houses and the artificial mineral water manufactory occurred at a time of economic growth and were likely participants in that growth. If the spa era at Brighton had such a limited effect, then the causations of seaside tourism at Brighton lie elsewhere. What were the factors that precipitated Brighton into a growth period during the 19th century? These questions are considered in the following chapters. Chapt 5 follows: Email: bruce@thespas.co.uk (click here to send an email) ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

CLICK THE FISH BELOW TO EXTEND YOUR EXPLORATION OF BRIGHTON  Brighton's Past on Shifting Sands Part ONE.  Brighton's Past on Shifting Sands Part TWO.  Brighton's Past on Shifting Sands Part THREE.  Brighton's Crimean Cannon.  The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway.  The Last Fisherman - Rory's Grotto.  Tourism and the Sussex Downs - South Downs National Park.  Crystal Palace - a key tourist location between London and Brighton. DESTINY CATEGORY 18th CENTURY second half, 19th CENTURY first half, 19th CENTURY second half, 20th CENTURY - second half, Historical summary FACILITIES Access all Year, Access by Road, Access on Foot, Hotel or B and B Facilities, Part of a larger tourism attraction, Restaurant/Food, Retail Souvenir Shop, Toilets, Tourism Information LANDSCAPE Coastal, Urban |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||