|

CLIFTON HOTWELL SPA PAST AND PRESENT

THE GROTTO AT BRISTOL HOTWELLS

1877: THE SOCIETY OF MERCHANT VENTURERS and THE GROTTO.

by Bruce Tyldesley

Avon

United Kingdom

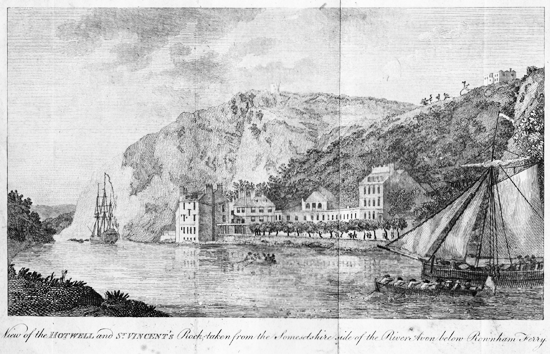

Although a prosperous property, in 1867 Hotwell House (built in 1822) was demolished so that Hotwell Point could be removed, in order to straighten the river making it safer to navigate. Inside Hotwell House was the Pump Room, which was the main public outlet for the Hotwell Spring. In 1866, the Society of Merchant Venturers sold Hotwell Point, Hotwell House and Hotwell Spring to the Docks Committee with a lot of other property in the Cumberland Basin area, which was then demolished to straighten the approach to the 1865 lock which was completed in 1873, and the one in use today.

There followed a public outcry by the People of Bristol because they had lost the Spa that had been one of its chief sources of early wealth and Clifton?s early fashion, which made the city famous. There had already been a public outcry in 1822 when Old Hotwell House had been demolished. The poor had always been allowed to draw Hotwell Spring water from the free tap, which was set up in a back yard, to conform with the prescriptive right of Bristolians and Cliftonians to have free access to the Hotwell. This free tap was in fact removed in 1831, but another was set up in 1837 as a result of threatened legal action by a section of the Bristol public. However, this was lost again in 1867, when Hotwell House was demolished.

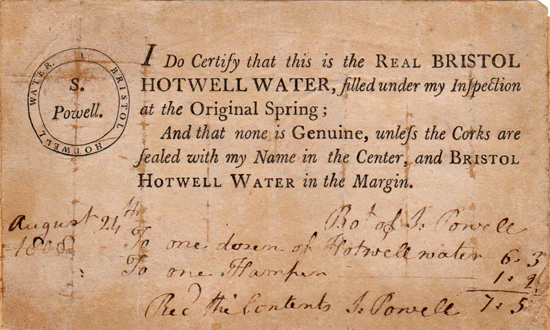

Picture above - Hotwells bottled water label August 21 1808.

There was, of course, a but in the Spring part of the property transaction between the Society of Merchant Venturers and the Docks Committee, because the Merchant Venturers had retained the rights to all wells, springs etc. on the land and the right to sell the water, including the Hotwell. Following the public outcry in the beginning of the 1870s, the Society of Merchant Venturers requested the Docks Committee to hack out the Grotto at the base of St. Vincent's Rocks.

The Grotto was a man-made cave supplied with piped water from the Hotwell to be available for the general public. The entrance to the cave was framed by an arch of rusticated masonry, and contained an ornate cast-iron pump donated by the Merchant Venturers. The pump itself had a decorative central panel with the image of a foliated mans face, through whose open mouth the water could be pumped. Around the mans head were stylized dragon flies and the handle of the pump resembled the body of a huge dragon fly. The pump was surmounted by entwined dolphins or sturgeon and crowned by Neptune's or Britannia's trident. Like Joseph Rendall's 1723 statue Neptune, erected on the site of the old reservoir of Temple Conduit, it was a powerful symbol of people's right to clean water. The design of the dolphins was similar to the 1870 Lamp standard with dolphins by G. Vulliamy on Victoria Embankment, London, planned by the famous engineer Sir Joseph Bazalgette, who also incorporated a series of Vulliamy's dolphin lamps and benches to line the River Thames on the Albert Embankment, next to what remained of Vauxhall Spring Gardens, in London.

Above: original front elevation and section of the Grotto on Hotwell Road.

Drawing by Bruce Tyldesley.

Note: in 1946, the cast-iron pump was removed to the Underfall Yard of Bristol City Docks, and in 1961 there were reports that it had been donated to the City Museum.

Above: original front elevation and section of the Grotto on Hotwell Road.

Drawing by Bruce Tyldesley.

Note: in 1946, the cast-iron pump was removed to the Underfall Yard of Bristol City Docks, and in 1961 there were reports that it had been donated to the City Museum.

One of the more elderly employees of the Docks Committee acted as attendant, or resident hermit, as advertised by one guide book of the day. There was an 18th century tradition that hermits resided in grottos. However, the hermit in this grotto was more significant than this, because he also represented the real hermit who, according to an ancient legend attached to the Avon Gorge, lived in Vincent's cave, and caves under St. Vincent's Priory, during the Roman occupation of Britain. The Grotto was opened in 1877 and served the public.

A notice board in the cave read as follows:

This spring belonging to the Society of Merchant Venturers is open for the use of the public. Any person is free to drink of the water of this spring and to carry it away in jugs or bottle without payment. In order to prevent injury the Corporation have appointed an attendant to take charge of the pump and the spring. Such attendant may charge one halfpenny of any person requiring from him the use of a glass for drinking the water.

The Victorians linked water pollution with disease, and the River Avon was becoming increasingly polluted. There had been written documentary evidence, from as far back as ancient Rome, of people bathing with open wounds in public baths and later dying from infections. From about 1850 onwards, the Merchant Venturers developed strategies to relocate the Spa away from Hotwells and the river, up to Clifton.

They started by making an unsuccessful attempt to float a water company with Bristol Water Works, to capitalise upon springs in Clifton. At one time every house in Clifton had its own water well. Later, some people took shares in Clifton springs, such as Sion Spring, Richmond Spring, All Saints Spring and Jacob's Well. However, public springs and wells often ran dry in summer months, so pumps and reservoirs were needed to extract the meagre supply and store water in tanks for communal use. Sometimes these tanks were sabotaged. Drought months affected the whole of Bristol, including Redcliffe Pipe Spring, Neptune Spring and Barrow reservoir. As the population grew, many springs and wells became contaminated by cesspools that existed to capture sewage, before Victorian sewers were built. Cesspools soaked through porous rock and seeped into wells.

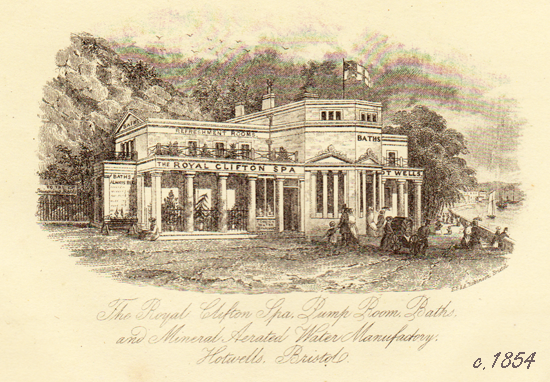

After the loss of The Royal Clifton Spa in 1867, the Society of Merchant Venturers sought counsel to build a Spa Pump Room, a new public outlet for Hotwell Spring, at the top of the Avon Gorge, near the summit of St. Vincent's Rocks, on Sion Hill, which had been their original location for the Clifton Assembly Rooms back in 1792, instead of The Mall. In any case, the Clifton Assembly Rooms, which were originally intended as a public venue for Bristol, by 1855 had been taken over by The Clifton Club, and no longer a public venue at all. The Merchant Venturers wanted to restore the once famous Spa to the city of Bristol because they believed it would provide employment, draw visitors and wealth back to the city and provide a boost to the local economy, bringing here a large number of visitors and possibly residents from all parts of the country, and so materially contribute to the future success and prosperity of Clifton. Since the removal of Hotwell Point, the bottom of the Avon Gorge was becoming increasingly busy with traffic, and they believed the air in Clifton was purer because it was removed from the bad smell of sewage in the polluted river, and charged with ozone from the Atlantic. Therefore, Clifton was regarded as a more salubrious situation for visitors to the Spa. Unlike the London Spas, Bristol had the Avon Gorge, which was still recognised as a place that provided naturally beautiful scenery with a romantic assemblage of woods, rocks, water, pasture and down, which could be capitalised upon.

Not only was the city of Bristol expanding but also people's ideas and understanding of the natural world around them was changing, combined with advancements in science and technology. This combination of art and science in the Age of Enlightenment, was epitomised by the Victorian Empire, and expressed quite early on in 1841, by the building of the Royal Albert Hall (one year after Queen Victoria married Prince Albert), which was originally supposed to be called The Central Hall for Arts and Sciences. The building of The Clifton Spa Pump Room and Clifton Rocks Railway might be seen as the antithesis of this, because it combined the high art of restoration of the historic Spa, using high technology of the day to achieve its purpose. In the late 18th century, artistic study and drawing of classical antiquity was exemplified by the eclectic grand homes of important people, such as the architect Sir John Soane (1753-1837) at Lincoln's Inn Fields, London (now a museum), and by the antiquarian collector George Weare Braikenridge (1775-1856), who commissioned mainly local artists to produce 1400 drawings, including some by the Bristol School of Artists (now at Bristol Art Gallery), for his home in Brislington, Bristol (now gone).

When combined with the Clifton Rocks Railway, which carried passengers from the banks of the River Avon, up a steep incline through a tunnel, to the Clifton Spa Pump Room near the summit of St. Vincent Rocks, it might be compared in concept to the Budapest Syklo. Opened in 1870, the Budapest Syklo was built at the start of a golden age in the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1896-1914), and was also accredited to George Marks. It carries people up from the river Danube, from Buda's narrow medieval streets, to Pest's grand 19th century boulevards to Buda Castle. This ancient Royal castle, or palace of a succession of Hungarian Kings, was redeveloped at the beginning of the 18th century in the Baroque style. It was the second funicular in Europe, the first being the underground funicular in Lyon. Lyon's first funicular was built in a tunnel, opened 1862, that carried people to Boulevard de la Croix Rousse or Russet Cross. Lyon was originally a Gaelic hill fort settlement, named after the Celtic god Lugus (see Chapter 6). In Paris, the Funicular de Montmartre was opened in 1900, and carries people up from the base of Montmartre to the church of Sacre Coeur Basilica. Montmartre was originally situated just outside Paris, and a likely Celtic druidic hill because of its high altitude. Christians were martyred on Montmartre during the Roman occupation of Paris in Gaul; one of them was St. Denis, martyred in AD 250, who became patron saint of France. A shrine, then a medieval church was built on the hill. Sacre Coeur Basilica was built between 1876 -1912, after the French Revolution, in the style of the Baroque Revival, and funded by public subscription. A mosaic in the apse entitled Christ in Majesty is among the largest in the world.

By the end of the 19th century, Queen Victoria, who in 1851 had granted Royal title to the Royal Clifton Spa, was held in great esteem by many important societies, and influenced many wealthy individuals who had been born, and whose wealth had been accrued, during her reign, and who proved loyal to her. She was also head of the Anglican Church, that was experiencing a cycle of catholic revival in the form of the Oxford Movement, which was started through the Ecclesiological Society, founded in 1839. The Oxford Movement set out to revive historically authentic Anglican worship and ceremonial, to restore medieval churches and supervise the building of new churches. It inspired our understanding and appreciation of English Medieval Art as we know it today.

Alexander Beresford-Hope, later MP for Maidstone and son-in-law of the Marquis of Salisbury, supervised and sponsored, on behalf of the Ecclesiological Society, the building of All Saints, Margaret Street (within a few yards of Oxford Street), in London, and All Saints, Clifton, in Bristol (blitzed in WWII). Standing on the site of Saint Margaret's Chapel, where in 1830 Frederick Oakley began to put into practice the teaching of the Oxford Movement, All Saints, Margaret Street, was designed by William Butterfield, on the principles of John Ruskin's purest form of Perpendicular Gothic, and was completed in 1859. The interior contains glorious imagery (recently restored by All Saints Foundation), including friezes of saints in ceramic, an abundance of mosaic in alabaster and marble, patterns in brick and tiles covering every surface, and painted images. The cavernous chancel and sanctuary, with flight of steps and banks of Baroque candlesticks, contains a silver Sacrament House, in the shape of a miniature silver model of the tiered steeple of St. Bride's church, which hovers aloft and is lit from within, shining like a solitary star in the night sky before the vast gilded reredos. Stray beams of sun light that struggle through dark stained glass almost seem an intrusion. St. Bride's steeple (said to have been the inspiration for the modern tiered wedding cake) carries the light of Christ over the high alter; this is perhaps a symbolic acknowledgement of Bride's special place in the ancient history of the British Isles, her star in the heavens is a reflection of Christ's, and she bestows her blessings and mercies, similar to Mary, the Mother of God. Apollo, or the sun, is recognised as being incorporated into Christian Medieval Art by the halo, a symbol that reflects Christ's divinity; the sun was also often incorporated into designs of the monstrance, which is used to carry and exhibit (display) the Host during the blessing, in catholic worship. 1851 was the year of, the foundation of the religious Community of All Saints Sisters of the Poor, who were attached to the church in central London. They, like other communities set up at that time, recognised flagship days within the historically authentic Anglican Church calendar, and re-kindled the old pilgrimages to places such as Walsingham and Glastonbury. Not only was there a revival of interest in old saints, but also the ancient shrines, sacred springs and Holy Wells attached to them. By the end of the 19th century, Victorian Gothic Revival was well established.

In 1851, Hotwell House had just been given the title Royal Clifton Spa, at the bottom of the Avon Gorge. In the same year the Merchant Venturers sold a plot of land to Sarah Hilhouse, and in 1862 they sold two plots of land and two houses to Abraham Hilhouse, George Bush, Robert Hilhouse Bush and James Bush, at the top of the Avon Gorge. It wasn't until 1891 that these three plots of land and two houses became available; The Gloucester District Land Registry tells us that these were namely numbers 14 and 15 Prince's Buildings, with a plot of land on the corner of Prince's Lane and Sion Hill. It was this plot of land and properties which the Society of Merchant Venturers eventually persuaded George Newnes to buy, for the purposes of building their Clifton Spa Pump Room, at the top of the Avon Gorge, in Bristol.

George Newnes was a very wealthy individual who proved willing to take up the mantle and re-build the historic Hotwell Spa, in Clifton, which he financed entirely himself. George Newnes commissioned a principal engineer and architect who were capable of carrying out the work. They were George Marks (engineer) and his colleague Philip Munro (architect). At the original 1694 Old Hotwell House, a pump was constructed that was capable of raising the water 30 feet, the 1822 Hotwell House was supplied with Hotwell water through a borehole about 60 feet deep, located near the 18th century Colonnade. In 1894, two hundred years after Old Hotwell House, the fountain in the Clifton Spa Pump Room was supplied through a much deeper borehole that drilled through the height of the Avon Gorge, and down considerably deeper than any previous borehole, next to the Colonnade, to tap the Hotwell. The Clifton Rocks Railway was located next to the Pump Room so as to provide a means of public transport that linked Hotwells and the City of Bristol, with The Clifton Spa Pump Room, and provided a link to Clifton, and Clifton Suspension Bridge as a means of crossing the Avon Gorge. In 1895, one year after The Clifton Spa Pump Room and Clifton Rocks Railway were completed, Sir George Newnes was made a Baron.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

GREAT BRITISH GROTTO GRADING

Click to go to Grotto.Directory home page

|